WILD HEART MUSTANGS™

|

|

COMING IN THE JUNE ISSUE of the WILD HEART MUSTANGS™ e-zine:

|

|

Brigid O'Donahue, founder of the United Special Sportsman Alliance (USSA), tells us how alliance sportsmen help make wishes come true for sick or disabled children and adults by OPENING THE DOOR TO THE GREAT OUTDOORS.

|

About On My Ass, by Lou Dean:

On My Ass is not only the story of a woman riding across Colorado to promote nonviolence in schools or her personal journey from within. This book touches the soul of being a partner with her donkey, Jesse James – it's about listening, about growth, about understanding – between her and Jesse, within herself and the discovery of it with a higher power. Her journey is inspiring in many ways: the hardship and distance, the obstacles (both physical and emotional) that are overcome, and the people she and Jeanne meet along the way who give a renewed faith in mankind.

Fishing Event held by the United Special Sportsman Alliance (USSA)

|

LOU DEAN is the four-time Winner of the Western Heritage Award; the creator of the Emmy-Award Winning Kung Fu, ABC-TV Series; creator of the Emmy-Award Winning The Young Riders ABC-TV Series; and co-Creator of Dead Man’s Gun, MGM/Showtime TV Series

From the cover of On My Ass:

In a passionate attempt to make a differece, Lou Dean saddles up her donkey, Jesse James, collects her riding buddy Jeanne, and rides off across the width of Colorado to promote non-violence in schools. As they face unforeseen challenges along the trail, Lou Dean wrestles with the brokenness of her past and seeks the courage to stay in the saddle. |

Click on image above to purchase On My Ass and other books by Lou Dean

|

ON MY ASS - RIDING THE MIDLIFE CRISIS TRAIL

High Plains Press

by Lou Dean

Excerpt 1

I thought back to the day I’d finally found a way to keep my ass from folding up his legs and hitting the dirt with me in the saddle. In the beginning, I had no idea now to break him of the trick, so I’d asked everyone around the country. Most trainers didn’t know, because they’d had little experience with donkeys.

Finally an old cowboy that worked up on Three Springs Ranch near Massadona had an answer for me.

“Have you a blanket in front of you on the saddle, where you can get to it real quick,” he said, hesitating and switching his chew from one check to the other. “When he hits the dirt, you take that blanket and cover his eyes and sit on his neck so he can’t get up.”

“Really?” I asked. I remember thinking to myself, “How can something that simple break him of going to the ground?”

But I took the advice and the lesson worked like magic. The next time Jesse put his head down and went to the ground, I jumped off, put the blanket over his eyes, and sat on his neck. He didn’t like it at all and immediately tried to get up. Of course, he couldn’t get up with me on his neck.

While I sat on his neck, Jesse moaned and grunted and complained loudly. He wasn’t hurting, just mad. I made him stay in that position until he was wet with sweat. And that was the last time he ever went to the ground with me.

But even after the harsh lesson, he would still stop, put his head down, and think about it. The head would go down and we could see those big eyes flashing with thoughts: “I want to go down.” But then the head would snap back up and he’d catch a gear: “I don’t want that blanket over my head.”

The process had been a source of great amusement to Jeanne and me. I had learned that donkeys are much smarter than most horses. Once they learn a lesson, they never forget. The other problem I’d had over the years riding my donkey was his tendency to balk. I rode him with spurs, but I seldom had to gig him in the flanks. He was smart enough to know when I had the spurs on and usually that’s all it took. I had learned that punching him gently with the spurs worked unless there was something going on with him that I didn’t understand. It was a continual challenge trying to decide whether Jesse was truly scared or hurting, or if he was just being a jackass.

But after working together for more than ten years, my donkey had taught me to pay attention to his radar. Like the day I was riding alone north on Blue Mountain and he came to a dead stop, head down right in the middle of a grassy meadow.

I kicked him in the flanks. His head dropped closer to the ground.

“Damn it, Jesse,” I said out loud. “I know you aren’t tired. What’s wrong?”

I kicked him harder, gigging him with the spurs. His body froze in place. I sat for several minutes, trying to understand. I looked around for any sign of danger, maybe a mountain lion on the nearby ridge.

Finally, I dismounted, took a step forward and let out t gasp. Less than a foot in front of Jesse was a deep open well. Possibly and old uranium mine, the hole was large enough that we could have fallen in and never been found. … I rubbed my donkey’s neck, walked him around the well, and praised him over and over.

“You truly are a Smart Ass,” I told him.

I thought back to the day I’d finally found a way to keep my ass from folding up his legs and hitting the dirt with me in the saddle. In the beginning, I had no idea now to break him of the trick, so I’d asked everyone around the country. Most trainers didn’t know, because they’d had little experience with donkeys.

Finally an old cowboy that worked up on Three Springs Ranch near Massadona had an answer for me.

“Have you a blanket in front of you on the saddle, where you can get to it real quick,” he said, hesitating and switching his chew from one check to the other. “When he hits the dirt, you take that blanket and cover his eyes and sit on his neck so he can’t get up.”

“Really?” I asked. I remember thinking to myself, “How can something that simple break him of going to the ground?”

But I took the advice and the lesson worked like magic. The next time Jesse put his head down and went to the ground, I jumped off, put the blanket over his eyes, and sat on his neck. He didn’t like it at all and immediately tried to get up. Of course, he couldn’t get up with me on his neck.

While I sat on his neck, Jesse moaned and grunted and complained loudly. He wasn’t hurting, just mad. I made him stay in that position until he was wet with sweat. And that was the last time he ever went to the ground with me.

But even after the harsh lesson, he would still stop, put his head down, and think about it. The head would go down and we could see those big eyes flashing with thoughts: “I want to go down.” But then the head would snap back up and he’d catch a gear: “I don’t want that blanket over my head.”

The process had been a source of great amusement to Jeanne and me. I had learned that donkeys are much smarter than most horses. Once they learn a lesson, they never forget. The other problem I’d had over the years riding my donkey was his tendency to balk. I rode him with spurs, but I seldom had to gig him in the flanks. He was smart enough to know when I had the spurs on and usually that’s all it took. I had learned that punching him gently with the spurs worked unless there was something going on with him that I didn’t understand. It was a continual challenge trying to decide whether Jesse was truly scared or hurting, or if he was just being a jackass.

But after working together for more than ten years, my donkey had taught me to pay attention to his radar. Like the day I was riding alone north on Blue Mountain and he came to a dead stop, head down right in the middle of a grassy meadow.

I kicked him in the flanks. His head dropped closer to the ground.

“Damn it, Jesse,” I said out loud. “I know you aren’t tired. What’s wrong?”

I kicked him harder, gigging him with the spurs. His body froze in place. I sat for several minutes, trying to understand. I looked around for any sign of danger, maybe a mountain lion on the nearby ridge.

Finally, I dismounted, took a step forward and let out t gasp. Less than a foot in front of Jesse was a deep open well. Possibly and old uranium mine, the hole was large enough that we could have fallen in and never been found. … I rubbed my donkey’s neck, walked him around the well, and praised him over and over.

“You truly are a Smart Ass,” I told him.

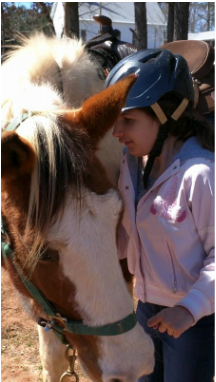

EQUINES - THERAPY FOR EVERYONE

|

Sara Carter is the Founder and Executive Director of the Haven Hills Therapeutic Riding Center in Fairborn, Georgia, She's also Accounts Manager at Peek Lawn Service and a licensed massage therapist at Atlas Massage.

|

|

Sara Carter & Dillon at the Special Olympics

|

When you hear the words, “equine therapy” or “hippotherapy” you automatically assume there will be horses. What people don’t realize is that there is so much more than just “putting a disabled population” astride a horse. So much more. I can’t speak for any of the other therapy centers across the nation but I can speak for mine (Haven Hills Therapeutic Riding Center), what it is to me, our athletes (yes, they are the very definition of athletes), our horses, and our staff of volunteers.

Medically speaking, there are over 20 muscles that we do not use unless we are riding a horse or mimicking the motions at the gym. Every time they ride, our athletes are strengthening those targeted muscles; those muscles then get stronger and fill in where there are weaknesses. The core, chewing, head and neck control, legs and various other muscles start getting stronger due to the new support offered. Children whose parents were told to go home and pray start moving, talking, and responding in new ways. Disabled adults who are frustrated with basic cognitive abilities start feeling hopeful again. But why? To me, it is a spiritual thing. To me, the horse is so much more than just a carrier of our burdens. They are healers in and among themselves. |

|

Therapeutic riding helps the general exceptional needs population in more ways than strengthening muscles. It improves cognitive abilities, sensory integration disorders, social skills, calms anxiety, and so much more than I can touch on in one article. Aside from the exceptional needs and the disabled population, our rare form of therapy also helps our veterans, mental health patients, battered women and children and also at-risk youth populations. Horses provide immediate feedback with every step, brush stroke, and nicker. In our program, we use several rescued horses. Those horses know and understand what it’s like to have people let you down, abuse you, and even more horrendous acts of the human element. Almost instantly the horse will size its handler or rider up and know exactly what it’s dealing with. That’s where the magic really happens. Horses that may have been a little rough around the edges start tip toeing for a more fragile rider. Horses that are have been overconfident in the past start sharing and instilling confidence in others. You will see group dynamics (volunteers, handlers, horses, riders) with every different horse change time and time again because that’s what our horses do. They adapt for us, even when we cannot adapt at all. |

Adrian hugging Dixie

|

|

Cadence and her favorite penguin

Rachel at Special Olympics, giving

a thumbs up after her ride |

At Haven Hills, I see miracles (always more than one) every single session. They are far too numerous to list within this article, but here’s a list of my very favorites:

|

|

These are just a few of the millions of memories of our athletes, and for those that don’t know me I do cry alot. I’ve heard our volunteers repeatedly offer stories of how their work with our program has changed them. It’s made them more aware, more social, more fit, less afraid, you name it. It changes us all. And I personally am affected every day. It’s hard to believe that one animal can change so many people in such positive ways. They do.

People may think that any horse can be a therapy animal, and that’s partly true. A biting, kicking, mean horse can definitely teach a lesson or two in humility or even agility. What makes a good therapy horse? Patience. Kindness. Sturdiness. Strength. A sense of humor (yes, horses do have them). A work ethic that is unmatched by others. They have to be fearless and comfortable around medical equipment. They have to be patient when the athlete is having a very loud no good very bad day. The list goes on and on. It takes a special horse that understands its job, and that starts with us as trainers and owners. Some horses may not be appropriate for carrying our athletes, and that’s OK. Sometimes they just need to be there to be loved on by anyone that needs it. There’s a benefit to more than just riding them. |

Darby and her independence saddle

after her ride at Special Olympics |

|

Sherry and Rosie on the very

first day of class ever |

If you have an equine therapy center in your area, I highly recommend that you stop in and check it out. It’s unlike anything you’ll ever see again. If you can’t check it out, but want to help, send a friend. Many of them, like us, are non-profits and need all the help they can get. Donations of time, money, and supplies are usually in short supply and are appreciated by all of them. Take our horse, Buddy Bear: he loves his donations of sugar-powdered donuts every week. They’re the very thing he looks for when his athletes approach him. It doesn’t take much, every little bit helps, and the rewards are far more than mere words could ever begin to describe.

|

Haven Hills Therapeutic Riding Center - where

prayers are answered through caring people and special horses |