by Amy Ortez, DVM

|

|

A HEADS UP ON TICKS AND LYME DISEASE

by Amy Ortez, DVM

This time of year, I am frequently approached by equine owners on the topic of Lyme disease. There are misconceptions and I don't think the general public understands how ubiquitous infection is in the population and how rare it is to have clinical signs with a definitive diagnosis. So lets take a closer look at ticks, clinical testing and Lyme disease.

Lyme Disease

Most articles about ticks reference a 'blood meal.' This means that the little creepy crawling arachnids are feasting on mammalian blood, with their mouth parts buried in flesh. It is not as romantic as Bela Lugosi's Dracula or Edward and Bella's story in the Twilight series. None the less, ticks feast on blood and have a few defense mechanisms to help with their plight.

There are 24 classes of tick saliva proteins recently identified(1 ) but the proteins and peptides currently used to test for Lyme disease are C6, OspA, Osp C and Osp F. These are the antigens used to test for the presence of Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochete (spiral shaped bacterium) responsible for Lyme disease. These antigens induce an antibody response from the host (horse, dog or human). The ELISA (enzyme linked imunosorbent assay) and Western Blot tests detect the C6 antibody 3-6 weeks after exposure. A positive results means that the animal has been exposed to the spirochete. It does not detect disease. Quantitative tests such as the Lyme Multiplex (Cornell University) Lyme Quant C6 Test (IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME) can help define the significance of a positive ELISA or Western Blot and how well the individual is responding to therapy. The Lyme Multiplex is the most comprehensive test currently available. It measures the outer surface proteins (Osp) A, C and F of B. burgdorferi. A high Osp A value indicates recent vaccination. Elevated C values indicate recent infection and increased F values are found in chronic infections. In areas where Lyme is endemic, this information can help one decide it treatment is warranted and its efficacy. (2,3,4)

|

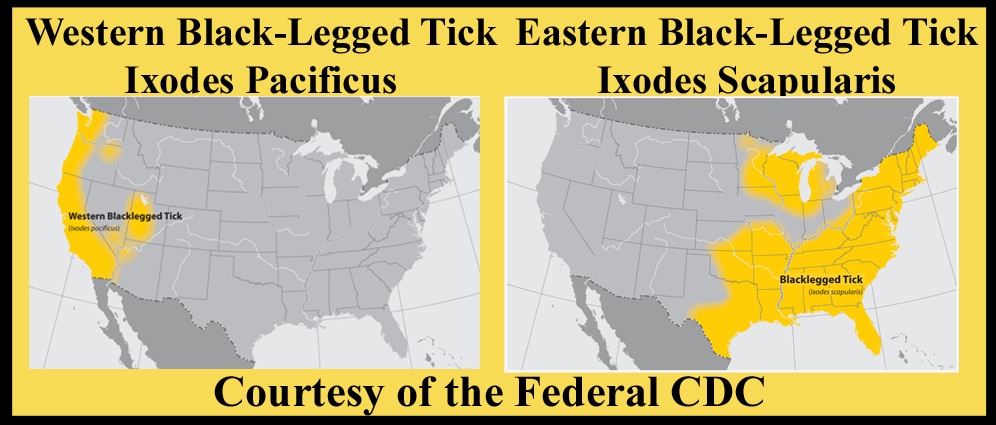

Ixodes pacificus (West coast)

|

While horse, humans and dogs can all develop clinical Lyme disease, there are some important differences. The eastern coast of the United States has the highest number of Ixodes ticks, the responsible vector for Borrelia. Depending on location, up to 77% of the equine population could have antibodies but not that many have clinical disease. How many show clinical disease is a matter of controversy. Clinical signs attributed to Lyme disease include lameness/stiffness, hyperesthesia (overly sensitive to touch), neurologic deficits, and muscle wasting. Unfortunately, there are many other ailments that could cause these signs. (4) |

In humans, the most common clinical sign is the erythema migrans, a migrating red rash that sometimes looks like a bull's eye. It usually occurs 1-2 weeks after the bite. Sometimes, in addition to the erythema or redness, people will experience fatigue or flu-like symptoms such as joint pain, muscle pain, and headache. Severely affected individuals (10%) may have neurologic signs, cardiac arrhythmias and arthritis that occurs weeks to months after infection. People who have been diagnosed with Lyme multiple times do not have chronic infections but in fact have had the unfortunate luck to be infected by a Borrelia infected tick twice. There is a condition known as post-Lyme disease syndrome where vague signs such as fatigue and malaise have continued 6 months or longer after treatment but there is currently no scientific evidence to support a diagnosis of chronic Lyme disease. (5) Dogs may have a prevalence of 50-90% depending on location but 95% of dogs exposed do not show any clinical signs. Lyme manifests in dogs as recurrent lameness, fever, kidney disease, anorexia and depression. Fever is more common in dogs than other species. In experimental models, neurologic and heart disease has not occurred. (2)

|

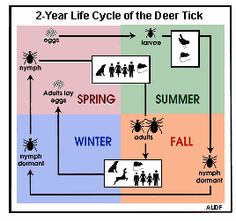

Treatment for all species includes antibiotics that also contain anti-inflammatory properties. It is the vague clinical signs, difficulty in testing for disease and not just infection, and the anti-inflammatory action of the antibiotics, that some claim lead to an over-diagnosis of Lyme disease. The spirochete is found in the midgut of the tick and requires 24-48 hours to travel from the midgut to the mouthparts during a meal. This means that if the tick is removed within 24 hours of feeding, the ability to transmit this disease is eliminated. The best way to prevent disease is to prevent the ticks from feeding. Frequent tick checks (especially arm pits, groins and around ears) will help decrease the likelihood of tick borne disease. There are Lyme vaccines licensed for dogs that have been used off label in horses. No vaccine for humans exists. |

Ixodes scapularis (East coast)

|

While this article may be dry, it is meant to explain why there are so many unknown variables in the diagnosis of Lyme disease and why it is difficult to confirm a diagnosis. Sampling cerebral spinal fluid can be more definitive, but that is not often practical. Treatment for horses can be very expensive so it is prudent to rule out other possibilities such as “normal” arthritis or endocrine diseases such as pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (Cushing's).

|

DISCLAIMER

The information contained on this website is not meant to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Information found on this website

is meant for educational and informational purposes only.

When in doubt, consult your veterinarian.

The information contained on this website is not meant to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. Information found on this website

is meant for educational and informational purposes only.

When in doubt, consult your veterinarian.